Methods

Sample Preparation and Analysis

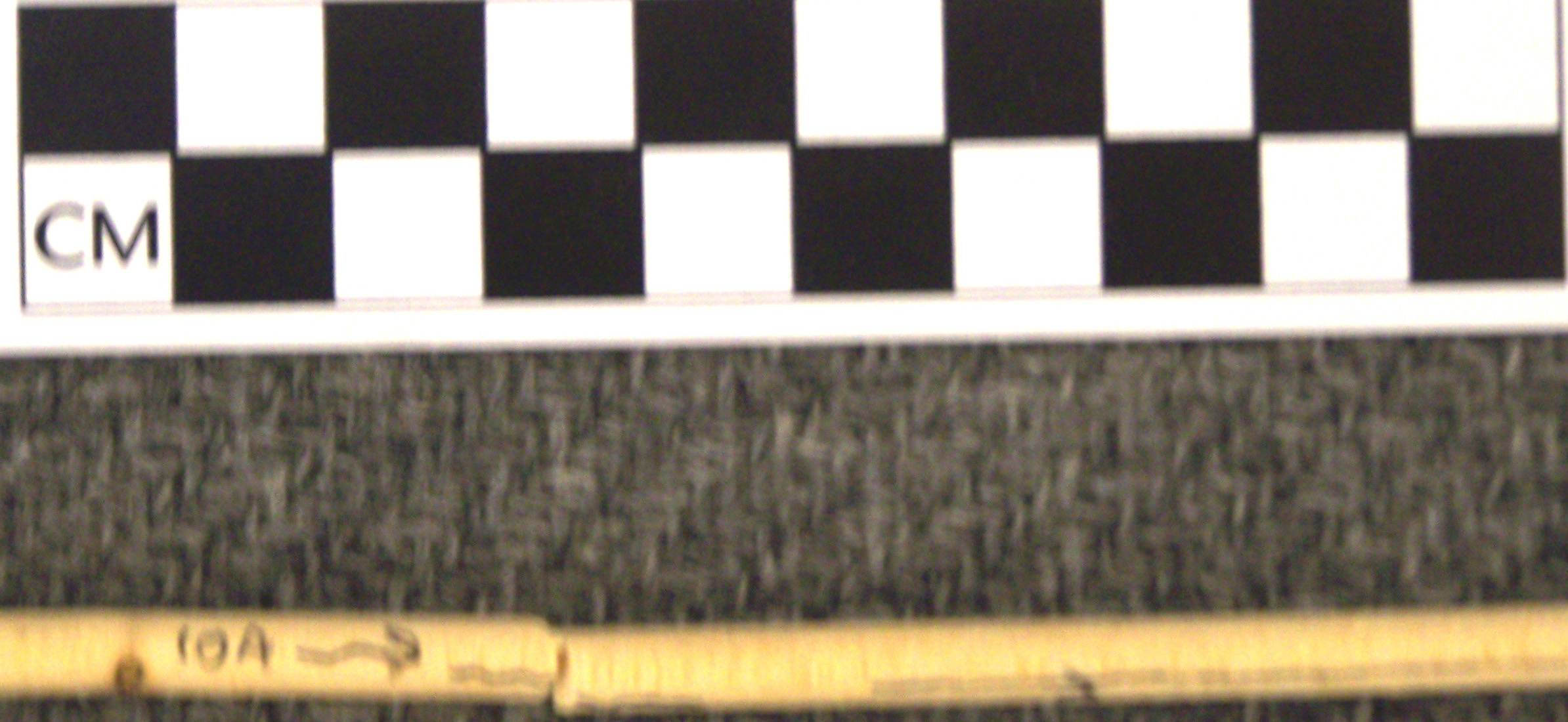

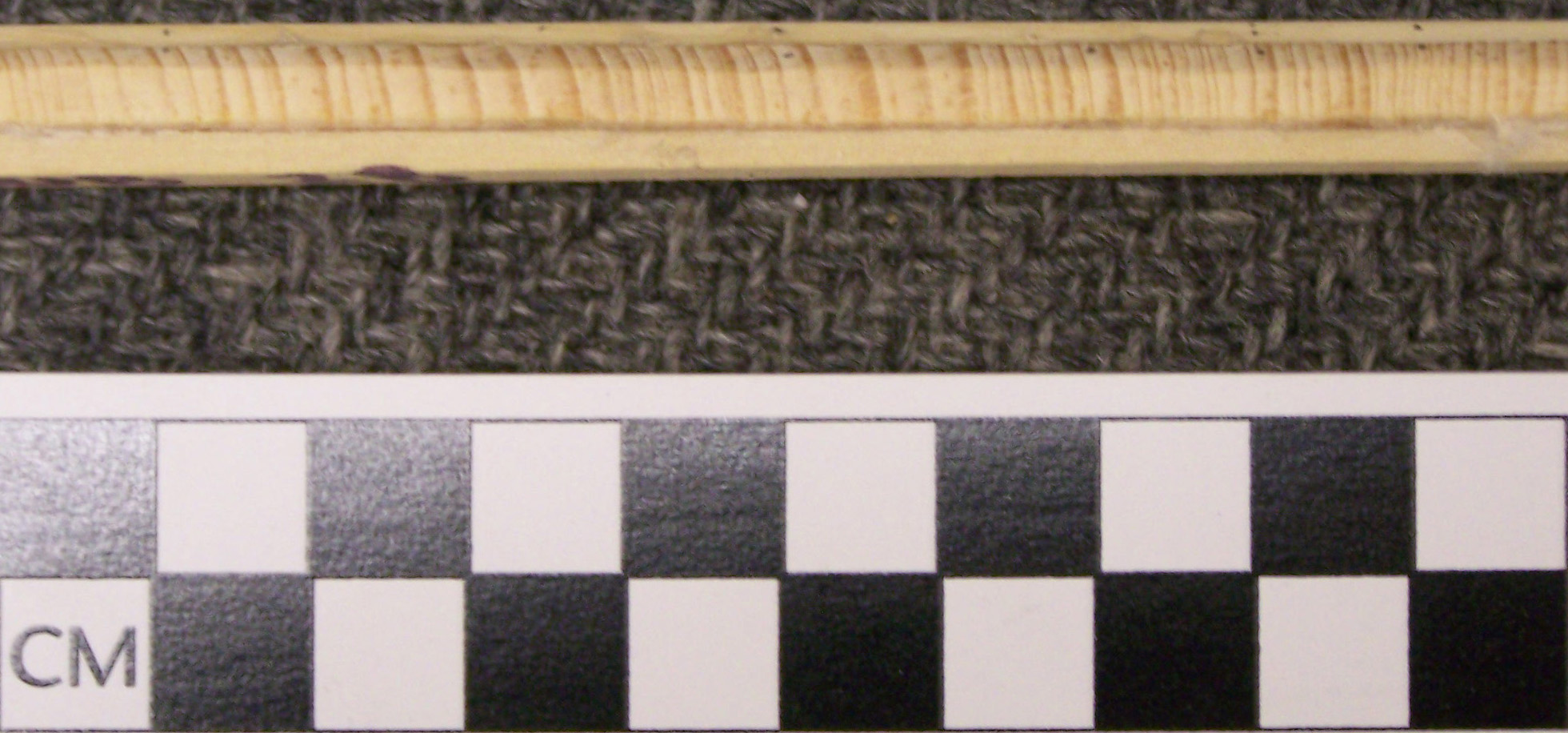

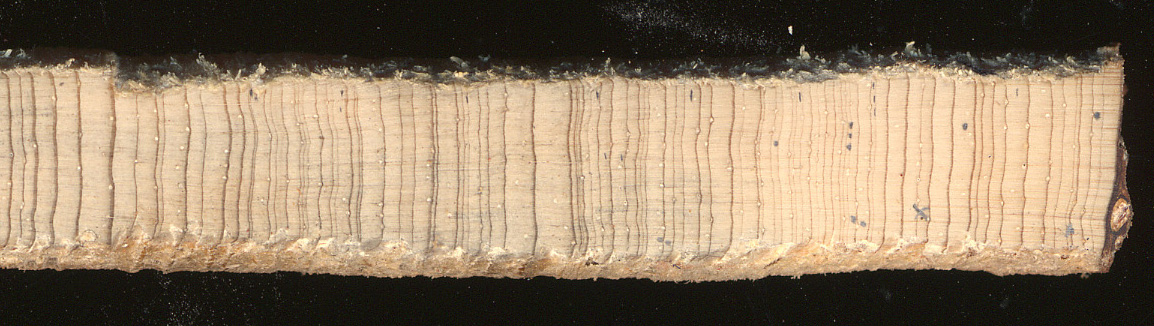

At the end of the field work, all tree-ring samples (living tree and archaeological) were transported to the LTRR in Tucson where they were prepared and surfaced according to long-established protocols (Stokes and Smiley 1968). Living tree cores were mounted in wooden core mounts [figures 5 and 6 ], and cut with a razor or sanded with fine-grit sandpaper to expose the ring structure. [figure 7 ] Archaeological samples, either cores or cross sections were sanded but not mounted. [figure 8 ]

Figure 5. An unmounted unsanded live-tree core.

Figure 6. A mounted and sanded live-tree core.

Figure 7. A high resolution scan of a live-tree core.

Figure 8. High resolution scan of an archaeological tree-ring sample.

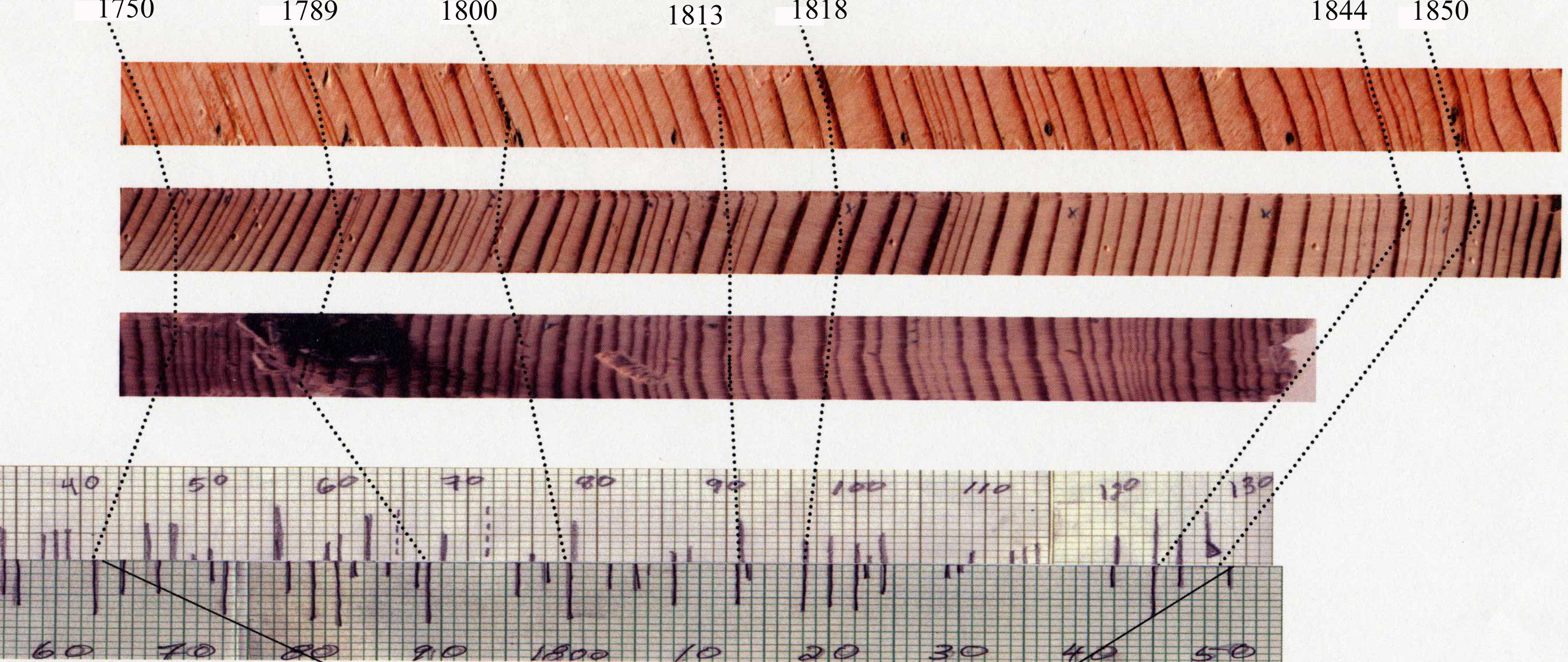

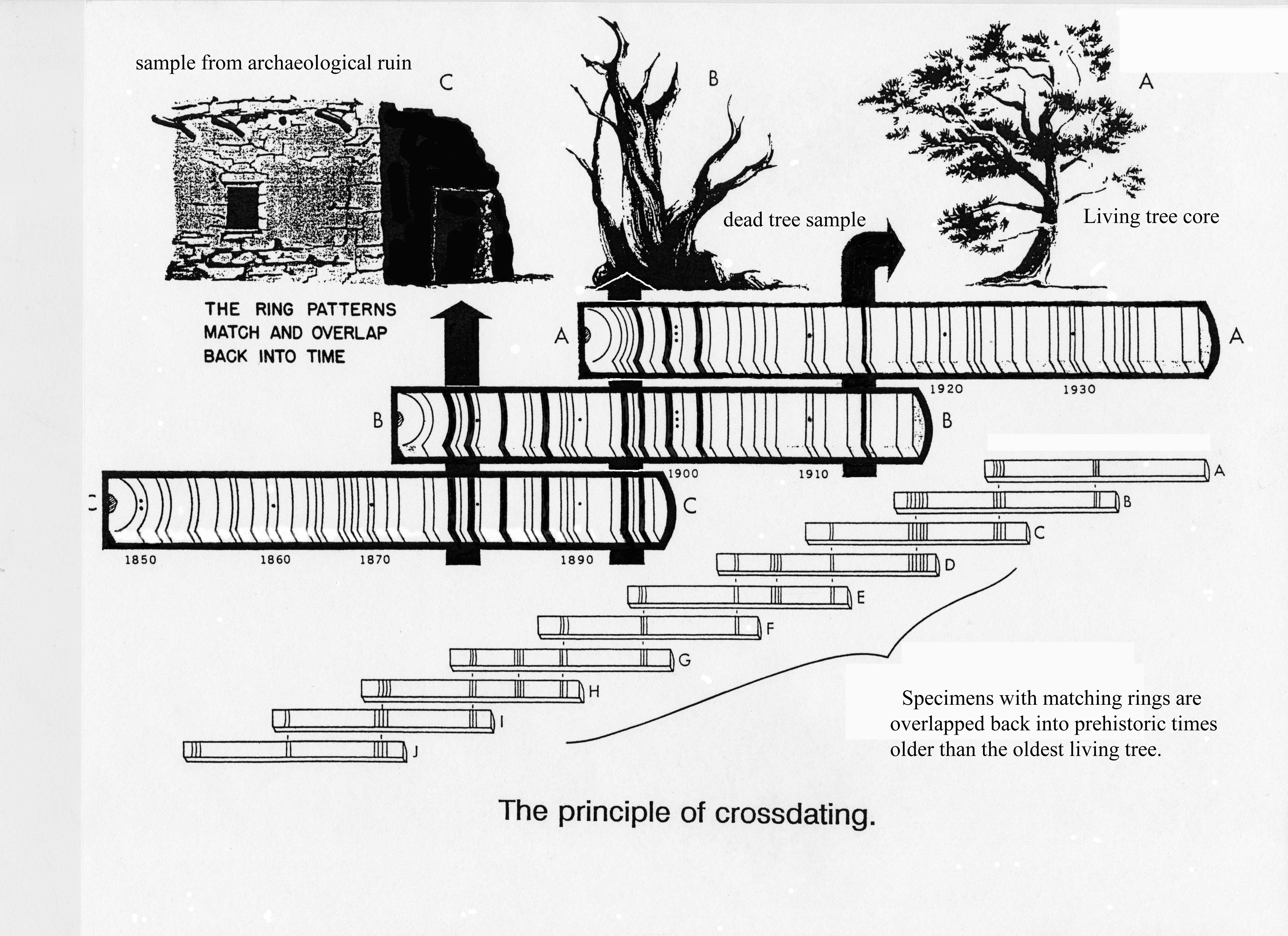

After preparation and surfacing, all samples were crossdated using the Douglass method of skeleton plotting (Stokes and Smiley 1968). This process allows us to assign Christian calendar dates to each and every ring on a sample by matching the pattern of wide and narrow rings. These patterns are then overlap back in time to form a Master plot against which individual samples can be dated (see figures below).

Figure 9.

Figure 10.

(Click the above figures to see larger pictures.)

Unfortunately, not all trees or archaeological samples produce dates. Some trees produce cambium in response to microenvironmental factors that are not reflected in the overall tree population; others respond to non-climatic factors such as nutrient availability; and still others do not produce annual rings.

In order to construct a chronology, the skeleton plotted samples from living trees, standing snags, remnant wood, and archaeological samples are combined into a master skeleton plot. By overlapping the plots of individual specimens, the chronology can be extended backwards in time until a lack of sample depth precludes crossdating.

Not all archaeological tree-ring dates are the same, however. Depending on the attributes of the outside ring on a sample, they may be termed cutting, near cutting, or noncutting dates. Cutting dates, also known as tree death dates, retain the last cambial layer grown by the tree and indicate that the tree was cut in a specific. Evidence on the sample that it is a cutting date includes the presence of bark, beetle galleries, patina, or a continuous ring around the sample (denoted by B, G, L, c or r in LTRR reports); a sample can also be considered a cutting date if the symbol "v" accompanies the date-- noting that in the opinion of an experienced analyst, the last ring on the sample is the last ring grown by the tree. Samples that yield cutting dates can also be assigned a cutting (death) season. Samples that exhibit a terminal ring with full latewood were cut after the growing season for that particular year ended. Samples that show only earlywood cells were cut during the growing season. Because different tree species have different growing seasons, cutting dates in a structure in the same year from different species can define construction of a building or room to relatively small time period, as little as a month in some cases.

Near cutting dates also retain the last ring grown by the tree; however, these particular specimens may (or may not) contain a locally absent or missing ring near the end of the ring sequence, and are indicted by a "+" symbol. For example, a sample that dates 1630-1848+B retains bark that indicates no exterior ring loss. However, 1845 was a very dry year in some area the Southwest and the 1845 ring is locally absent on many samples.. This hypothetical sample may crossdate from 1630 to 1842 and contain six additional rings after its last small "marker ring" of 1842. Because 1845 is typically small and often local absent on other samples, it may also be missing from this sample; therefore the last cambial layer on the sample may have actually grown in 1849, but there is no way to verify the absence (or presence) of the 1845 ring because the ring sequence does not extend far enough beyond 1848 to determine if it is locally absent or simply not small on this particular sample. Near cutting dates should be considered within a year or two of tree death dates.

Noncutting dates result from two different processes: exterior ring loss or ring counts near the outside of the sample ring sequence (and are denoted by "vv" or "++," respectively). Samples that do not retain the last ring grown by the tree (vv dates) have suffered exterior ring loss either through natural processes, such as erosion, or cultural processes, such as beam shaping. Thus, a sample dated A.D. 790-957vv could not have been cut prior to A.D. 957, but because it may be missing one, 10, or even 100 exterior rings from its outside. Partially ring counted specimens (++ dates) result from a lack of crossdating on the sample beyond a specific year. Ahlstrom (1985) suggests that "++" dates may indicate deadwood use because as trees die a slow natural death, they respond less and less to macroenvironmental conditions and produce more sporadic cambial growth layers. Noncutting dates (both vv and ++) provide only a terminus post quem, a date before which tree death could not have occurred; a noncutting date may predate the actual use of a beam by years, decades, or even centuries.